John Edward Lee, Charles Roach Smith and Aspects of Mid Victorian Archaeology

John Edward Lee, Charles Roach Smith and Aspects of Mid Victorian Archaeology

Jeremy Knight

|

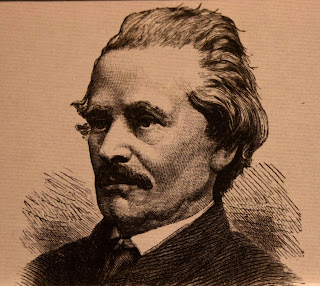

Charles Roach Smith, c. 1865 From

Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository This image

is on display at the British Museum. |

|

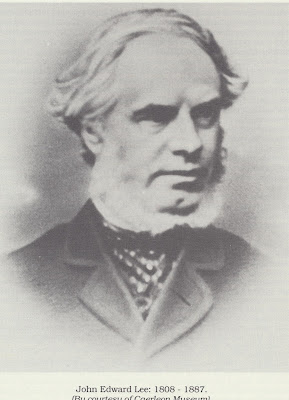

Picture of John Edward Lee copyright Caerleon Antiquarian Association |

Like Lee, Roach Smith never attended University, but

at the age of 14 started work in a solicitor’s office in the Isle of Wight. He

soon abandoned this and established a business as a chemist in London. His

scientific interests and business background have much in common with Lee, as both men were pioneers in what is now known as rescue archaeology, Smith

in London and Lee in Caerleon. When Smith moved to London in 1834 he found that

redevelopments in the City and the dredging of the River Thames were uncovering

large amounts of archaeological material which was being destroyed or lost

without record. By 1854 he had assembled a large collection. He established a

private museum and published A Catalogue of the Museum of London

Antiquities, followed by Illustrations of Roman London in 1859. His

collections later passed to the British Museum, where they formed the nucleus

of the Romano-British collections.

In 1843 Charles Roach Smith

and Thomas Wright founded the British Archaeological Associationn. The Society

of Antiquaries of London was seen as in the doldrums, with a largely inactive

Council and an absentee nobleman and politician as President, though both Roach

Smith and Wright were active Fellows. Soon after the establishment of the new

society however, what began as a dispute over publication of the inaugural Canterbury

Summer Meeting developed into ‘a prime example of a classic Victorian row’. By

1845 the two rival factions, the one led by Roach Smith and Wright, the other

by Albert Way, were holding rival conferences in Winchester, leading to an

eventual split and the foundation of the rival Archaeological Institute of

Great Britain and Ireland, now the Royal Archaeological Institute, with Albert

Way as Secretary. 3

Though several factors were at work, not least clashes of personality,

the whole episode had something of the onetime cricket fixture of Gentlemen

versus Players. One supporter of the Institute claimed that the British

Archaeological Association before the split ‘consisted of two distinct classes

of persons, the one gentlemen of property and amateurs of archaeology… the

other party consisting of professional archaeologists’. 4 Another

thought that learned societies should be in the hands of ‘men of rank or

property’ with private means and without the necessity of earning a living. The

term ‘professional archaeologist’ does not carry its modern meaning, for there

were virtually no salaried posts at this time, save for a few in the British

Museum. What the writer may have been referring to was the fact that both

Wright and Roach Smith published much material aimed at the growing taste for

archaeology and antiquities among the middle classes of Victorian Britain and

naturally drew an income from this. Roach Smith published a series of illustrated

volumes, Collectanea Antiqua , dealing with Roman and other sites in

Britain and northern France, which proved very popular..

Neither Roach Smith nor Lee

were university men and though Lee was certainly a ‘man of property’, with a

fine new house in the Gothic style in extensive grounds, (Tennyson assumed he

was a ‘landed proprietor’) he might still be thought of as being ‘in trade’. John

Edward Lee was born in Hull in 1808 to a wealthy family with shipping and

whaling interests. In 1841 he moved to Caerleon, as partner in the Newport firm

of J.J. Cordes, nail, spike and rivet makers at the Dos Works, known in Newport

as the ‘nail factory’ and as a hotbed of Chartism. Gwenllian Jones suggested

that his input was financial rather than technical. Lee was a talented artist

and draughtsman , fluent in French and German, in active touch with leading

scholars in those countries and with an expert knowledge of geology and

entymology. Like Roach Smith in London, he found that Roman finds were

constantly being discovered at Caerleon and then lost or dispersed without record. Roach

Smith recorded Lee’s efforts in characteristically forthright style

‘ For a long time, there has been an outcry against the neglect with

which the people of Caerleon have regarded their antiquities. Donovan, half a

century ago…… (attacked)…. the manner in

which these ancient remains were trafficked and carried away 5.

Williams, the author of a History of Monmouthshire in 1796 also exclaims

against the abstraction of the antiquities and suggests that a museum might be

formed at Caerleon ‘ The foundation of such a museum had been left to ‘a

gentleman who is not a native of the county’ 6

Before visiting Caerleon, Roach Smith called at Caerwent. One unread paper at the Canterbury conference had been an account of a visit to Caerwent in 1786 by the Bristol clergyman and schoolmaster Revd. Samuel Seyer. (see post below The Revd Samuel Seyer, a Visitor To Caerwent In 1786 ). Roach Smith reprinted this along with Seyer’s sketch map of the Roman town, the earliest known, preceeding Coxe’s surveyed plan by Thomas Morrice by almost twenty years. In Sayer’s time the villagers made money selling Roman coins to tourists –‘ Great quantities of Roman coins have been found here and are found every day, upon opening fresh earth. All which I saw (near one hundred) were Imperial……. I bought two very perfect copper pieces of Trajan, weighing about a penny each, for half a crown; among some smaller Roman coins I bought a silver penny of William the Conqueror and another of one of the Edwards’ 7

At Caerleon, Lee, like Tennyson eight years later, stayed at the Hanbury Arms, where the elderly landlady remembered the visits of Coxe and Colt Hoare. She said Coxe and Colt Hoare, ‘usually commenced their researches at four o’ clock in the morning in summer time’. Roach Smith called on Lee and the two of them visited Lee’s recue excavation of an extra mural Roman bath building which had been found in the landscaping of the Mynde. 8

|

| Caerleon Extra Mural Baths taken from Isca Silurum, or, an illustrated Catalogue of the Museum of Antiquities at Caerleon by John Edward Lee |

Several Roman inscriptions had recently been found and Lee was to describe these to ‘ The Caerleon Antiquarian Association, an institution recently founded by Mr Lee and his friends’.

|

| Caerleon Museum founded in 1850 Copyright: Monmouthshire Antiquarian Association. |

The quarrels which led to the foundation of the rival British Archaeological Association and Archaeological Institute reflected wider conflicts in mid Victorian society. There was rivalry between the established landed interest and the rising new industrialists, whose new money was seen as a challenge to the former’s social status. The Archaeological Institute contained many clergymen and architects more concerned with ecclesiastical architecture than with archaeological matters in the modern sense. There was also the conflict on a much wider stage between the claims of revealed religion and those of science, represented particularly by Charles Darwin. Happily, our own Association, with its strong local base, avoided such conflicts. Both the British Archaeological Association and the Royal Archaeological Institute , with their respective journals, still flourish. Long may they do so.

Jeremy Knight

1.

B Bowen,

E.I.P 1971 ‘The Monmouthshire and

Caerleon Archaeological Association ’ Archaeologia Cambrensis 120, 1-10

2.

Jones,

Gwenllian V.2001 ‘ John Edward Lee and

antiquarianism in nineteenth century Caerleon’

Monmouthshire Antiquary 17, 3-8.

3.

Wetherall,

David ‘ From Canterbury to Winchester: the foundation of the Institute’ in

Blaise Vyner (ed) Building on the Past: Papers Celebrating 150 Years of the

Royal Archaeological Institute (1994), 8-21

4.

J.H

Parker The Antiquary 4, 32-33, quoted Wetherall 17.

5.

E.

Donovan Descriptive Excursion through South Wales and Monmouthshire (London, 2 vols 1805)

6.

Roach

Smith, Charles 1849 ‘ Notes on Caerwent and Caerleon’ Journal of the British

Archaeological Association 4, 246-264 (at p 264).

7.

Op.cit.

248-253.